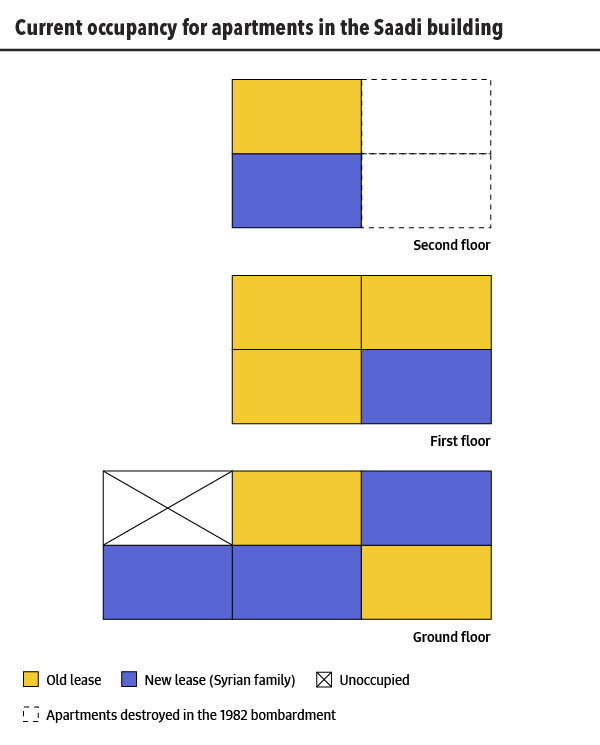

Many of Um Hassan's neighbors in the house and the neighborhood are leaving their homes, including Hajja Mahasen, who moved in with one of her sons in the Sports City area, and Um Yumna, who left Beirut for Barja. Um Hassan, like many of the families of Tarik Al Jadidah, inherited land and a portion of a house from her family outside of Beirut, in the South. But moving to the South wasn't an option for her. "We can't live in the south. We're not farmers. My son drives a taxi. What is he supposed to do in the south?" The family is composed of the two elderly parents and their two unmarried children. The family’s income depends on the only son, Hassan, who rents his uncle’s car to work as a taxi driver. The family's livelihood is thus fundamentally linked to their presence in the city, which provides the density required to operate a taxi as a main source of income. This dilapidated house, a part of which is located on land planned for a public road, ensures that the family can stay in the city and continue to sustain itself. But Um Hassan's family isn't the only one that has encountered a sense of stability, even if only temporarily, in substandard housing conditions. Um Hassan's former home in the Saadi building provides shelter for a family of seven displaced from Syria, and they're not the only ones. All of the apartments in the Saadi building whose residents were evicted now house Syrian families of six or seven people. Although the building will be demolished when all the old tenants are evicted, the displaced families have found safe haven in a precarious situation, enabling them to stay in the city near employment opportunities. Their presence in the building does not hinder the investor's efforts to demolish it, as evicting these families will be quicker and less complicated than evicting the old Lebanese tenants.

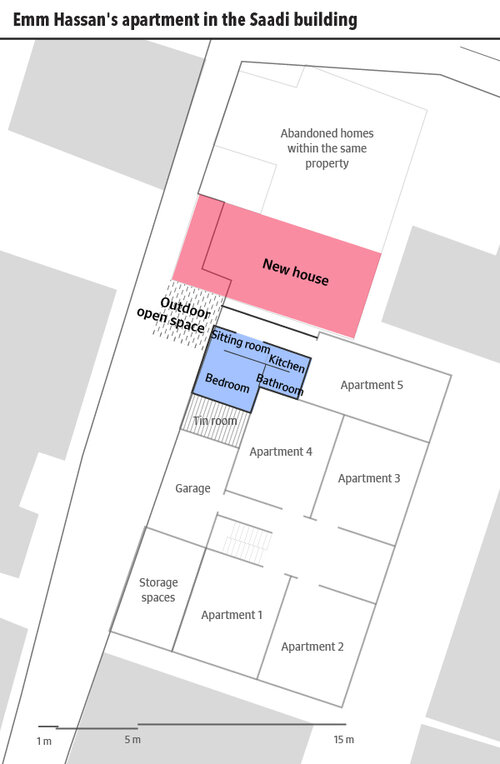

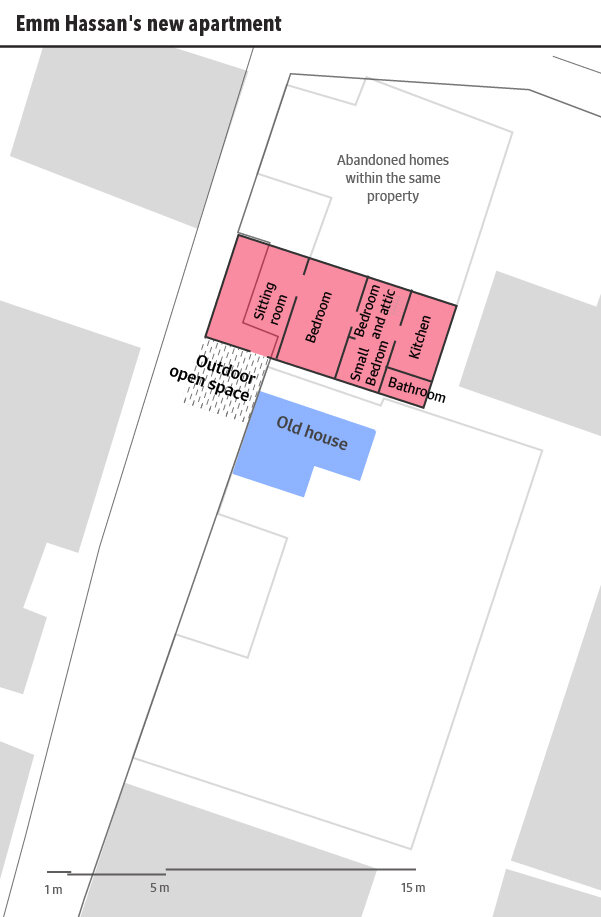

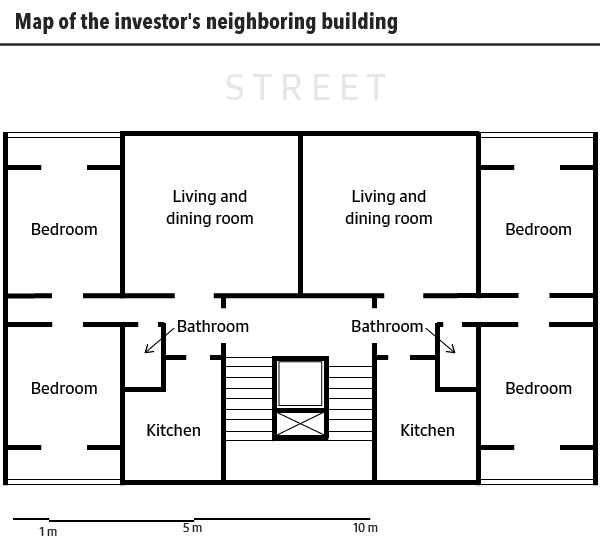

And so, while Um Hassan has remained in the neighborhood, it is the world around her that has changed. When she was a tenant, Um Hassan's ability to stay in the city was under constant threat by the inevitability of eviction. Today, as an owner, her presence still is not guaranteed. Um Hassan knows that the old, worn-down house that she bought is vulnerable because it could be swept away at any moment by the road planned nearby. In addition, Um Hassan's house is part of a larger property in which she has bought only a few shares. In counterpart, the remaining shares are owned by a number of inheritors. If they decide to sell it, she would find herself in the same dilemma. Like Nadia, Um Hassan and her family would have little say in the decision-making. The future of her housing situation would again be ruled by the compensation she would receive for her shares. Thus, the only sure thing that can be said about Um Hassan's future is that the Saadi building will be demolished, and her house will be adjacent to the new building's parking garage. Hala and her other neighbors will leave the neighborhood, and the open space would ultimately disappear. What are Um Hassan's chances of staying in the neighborhood now? And is her ownership of a piece of the property really a guarantee that she can stay?

Originally published in Arabic on the Housing Monitor.